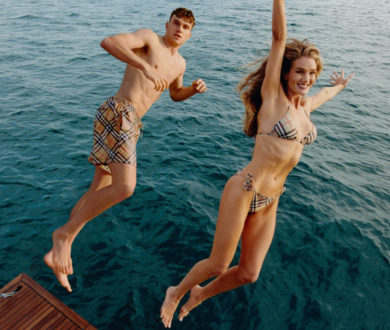

At 15 years old, Melanie Lynskey was plucked from her life in New Plymouth to star alongside Kate Winslet in Peter Jackson’s 1994 film Heavenly Creatures. Her performance as Pauline Parker was critically acclaimed, and the film itself eventually nominated for an Oscar. Since then, Lynskey’s varied and intriguing career has proved a strong exception to the rule of eventual burnout that so often hangs over actors who enjoy early success.

Going on to play a raft of crucial supporting roles in films like Coyote Ugly, Sweet Home Alabama (with Reese Witherspoon), Up In the Air (with George Clooney) and The Informant! (opposite Matt Damon), before landing a recurring role on Two and a Half Men, and the leads in a number of acclaimed indie films like Hello I Must Be Going, I Don’t Feel At Home In This World Anymore and Sadie, Lynskey is one of those rare actors in ‘Hollywood’ whose work is not only consistent but of a truly high calibre.

This is something the industry has also recognised, rewarding the actress with a Sundance Special Jury Award, a Hollywood Film Award and Critics’ Choice nominations. For Lynskey, it seems, the love for her work lies in the process as opposed to the outcome, which explains the way she has managed to steer her career through a notoriously fickle industry with such understated grace.

Having recently finished filming her role in upcoming blockbuster Don’t Look Up (with a cast that includes Meryl Streep, Cate Blanchett, Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence and more) and about to start production on an exciting new series for Showtime (with Christina Ricci and Juliette Lewis), Lynskey continues to go from strength to strength — a pattern we’re sure will continue to define her impressive career, well into the future.

Here, the actress divulges some of the lessons she has learned along the way, from listening to her instincts to the importance of diversity in film.

I am very much an introvert and I was painfully shy as a child, but the first time I was on stage in a school play, I felt this freedom being somebody else other than Melanie. It gave me a crazy confidence and it was such a powerful thing for me. I think I got addicted, because as soon as I would stop acting I’d go back to being that shy little girl. So I started to say it was what I wanted to do for a living and everybody was like ‘you’re crazy,’ and then I got Heavenly Creatures [with Kate Winslet and Peter Jackson] when I was still in high school.

You don’t just get a breakout role and become a ‘movie star.’ The people around me at the time, because they knew how hard the industry was, didn’t want me to get carried away. Everyone was like ‘go back to high school, get a degree and get on with your life.’ And I read it as a knock on my talent instead of them being protective, so I took some time to determine if it was what I really wanted to do.

I once auditioned to play Janis Joplin and I still sometimes wake up in a cold sweat thinking that there’s a tape of me auditioning to play Janis Joplin out there somewhere… so mortifying. It was when I was younger, and was auditioning for everything, so there were roles that I would go for that didn’t resonate with me, in my soul, and that was torturous. I mean I wish Janis Joplin was in me, but she really isn’t. Now that I’m older and am able to have a little bit more say, the roles I gravitate towards are the ones where I connect inherently with the character. Where there’s a part of me that understands this person and that needs to get their emotion out of my system. So the actual acting part becomes easy.

I know, when I read a script, if I can do it or not. The only thing I really do to prepare is something called creative dream work — it sounds very ‘woo woo’ but it works for me. You sort of channel the character and ask yourself for a dream, and whatever comes up in your dream you write it down in the morning. I get a lot of invaluable information that way, it could be a physicality or someone will be in the dream and I’ll realise how much of that person is in the character I’m working on.

I’ve only had one job when I didn’t have a dream. I was going through a horrible breakup and the script was about a horrible breakup, and my subconscious was like, I think you’ve got this.

It helps that I have good instincts and that I have learned to listen to them. I only do projects I am truly interested in. I have stopped letting myself consider movies that I don’t like because of the actors or directors that were apparently attached… the last time I did that, the actor I thought I would get a chance to work with (and the reason I did the movie) dropped out.

I had a therapist once who said, ‘why are you so good at advocating for your characters and not for yourself?’ It’s hard for me in my life to say that I feel upset about something or that I feel angry, and I don’t like being confrontational. But at work, if I get a note that I don’t like I’ll just say no, very clearly. And it can cause tension. Some directors want you to do exactly what they say but I know my characters so well, they’re a part of me, and I’ll stand up for them. I wish I could do it for myself too, but I’m not as good at that part.

I recently filmed a movie that my very dear friend Justin Long and his brother wrote and directed together and it is the silliest comedy. I played this woman who is a stoner and is visited by a ghost from the 1800s who teaches her how to be a lady. I had been doing a lot of intense stuff, and the thought of being in sweatpants and just acting like I was high for a whole movie was so freeing.

People think that all actors are millionaires. It’s so funny. Most actors are really struggling. There’s this website that publishes people’s net worths and they say mine is five million dollars and I’m over here thinking, ‘give me that money then, like where is it? Wherever it is, I’d love to have it.’

Often as an actor, if you dare say anything political, people get very upset and they say ‘oh well you’re one of the Hollywood elite and you live in your ivory tower.’ Most actors have come from nothing, and have had to work super hard to make their own way in the world. That perception that actors are out of touch and don’t understand what real people go through, it’s so strange to me. It’s not like we were just formed and put on the earth at 22 years old, we’ve lived life, we’ve had upbringings, we’re friends with a lot of different people even if we are working in film.

I try to use my platforms to draw attention to issues I care passionately about and I follow a lot of smart, politically active people on Twitter. Unfortunately, basic human rights are still something that need to be stood up for right now, for people of colour, for women, for gay people and trans people, and it’s nuts to me that we’re in 2021 and we’re still having to have this conversation.

Diversity is a big issue in my industry. But I do think people are starting to make changes. Especially in television, I’ve been working with so many more female directors. It makes the working days shorter because they’re more decisive — they don’t feel as though they’re allowed to take all the time in the world to make a decision. Not that all male directors are like that, many of them are empathetic and kind and collaborative, but in my experience, almost all female directors are those things. So that’s been a really nice change. I did a show a few years ago, Mrs. America, that was entirely directed by women, every episode. Having diverse voices and perspectives are so invaluable when you’re making art and for so long we’ve only seen the worldview of white men.

I have pinch-me moments all the time. I did a movie a few years ago that Steven Soderbergh directed, and he has always been one of my favourite directors. I’ve seen everything he’s ever done. So to have him think I was doing a good job and to be in that film with Matt Damon, playing Matt Damon’s wife, every day on that movie I was like… wait what?

I did a scene with Leonardo DiCaprio the other day… it was bizarre. He’s one of the very few famous people I’ve met who just seems like a guy, I really was not expecting that. There are famous people like George Clooney (who is one of the nicest people, by the way) who walk into a room and there’s an energy shift… and it’s not something he means to do — he doesn’t have a trailer, he doesn’t have a makeup artist, he hangs around with everybody on set — but there’s something about him.

Reese Witherspoon is another one — they’re movie stars. And so it was really interesting with Leo, that he came into the room and I didn’t notice for a minute. He carries himself with such modesty. It was inspiring to work with somebody who really is at the top of their game, but who was also so generous as an actor. His performance off camera for me was exactly the same as when the camera was on him. There was no holding anything back or trying to save it for his close up.

My favourite directors are the ones that trust me. I don’t like being micromanaged. Jay Duplass, who I did the show Togetherness with, said that if he went onto set and told his actors exactly how to do it and how to feel their emotions, it would throw them off so completely because they’re ready to let everything out they’ve been holding onto for months, and it confuses their instincts. If you let an actor do whatever they want for the first take, then you can give a million notes — but chances are, you won’t need to.

It’s a bummer to have to say this but the biggest challenge I’ve faced in my career would be my own body image and the way that the industry views people’s bodies. There’s sort of an implicit expectation of perfection because everybody looks the same but I had a bad eating disorder for 10 years and even when I was like 58 kilograms I would still be shamed in wardrobe fittings for not being sample size.

Or now that I’ve had a baby it’s like, ‘you should be proud of what your body has done’ and it’s upsetting that the only way women are allowed to not look perfect is if they have given birth. Plenty of women have never given birth and they should be allowed to look however the fuck they want.

I did a movie once [Hello, I Must Be Going], where I had a young love interest and a lot of the reviews were just men trying to process how I could realistically be sexually attractive to someone younger. Roger Ebert, god rest his soul, who was a wonderful reviewer, spent his entire review trying to understand how this man would want to have sex with me. He said that Chris Abbott (my co-star) was almost a good enough actor to make him believe it and that I was cuddly and sweet BUT… And I was like seriously? You don’t think that a bored 19 year old would want to have sex with me for the summer, like really? Is it that dire of a situation?

Recently I was on set with an intimacy coordinator. It’s something that’s around more after MeToo, someone who is on set to make sure the actors feel comfortable with an intimate scene. I wish I had had that when I was younger. There were a couple of times early in my career when I didn’t have enough agency to say that I was uncomfortable. I once had to do a scene where a man attacked me and tried to force himself on me and we had choreographed the whole thing with the stunt coordinator and then at the last minute, the actor and the director changed the choreography so it would look more ‘real,’ and it was so scary. I wasn’t even good in the take because I was so confused.

My measure of success was always whether or not I would have to pick up a second job. Being able to make a living in this industry without having to ‘fall back’ on something is an amazing thing, and I’m very grateful for it. Especially now, being in a position where I don’t have to audition as much and have a bit more choice. Sometimes, people on Twitter write to me saying ‘you should have a better career!’ but I feel good about it, myself.

My guilty pleasure is reality television. My fiancé and I watch The Voice, The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, Million Dollar Listing and all seasons of The Bachelor — even the first season of the New Zealand one. My fiance loved it. He couldn’t get over how low key the production was…. like when a girl had to drive herself to a date, he was shocked.

People would probably describe me as anxious. I had a therapy session with all of my siblings once, and they all said that I needed to worry less. My siblings make fun of me because ‘be careful’ is the last thing I say to them in emails or over the phone.

I would like to be remembered for being kind. That’s always my hope when I interact with anybody, that I could have made their day a little bit better. I just hope that when people think about me they think, ‘she was nice.’

Of everything I have done, I’m most proud of my daughter. I had her when I was 41 so I was a little late getting started but she’s two now and she is so funny and weird. It’s been a really corrective experience for me.

I’ve just finished doing a movie called Don’t Look Up which has this ridiculous cast [Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence, Cate Blanchett, Meryl Streep, Timothée Chalamet and more] and then I’m doing a drama/thriller series that has been picked up for Showtime called Yellowjackets with Christina Ricci, Juliette Lewis and Tawny Cypress. Half of it takes place in the 90s as our younger selves and half of it is today and we’re survivors of this plane crash where a lot of crazy shit went down.

At the moment I’m getting tested three times a week [for Covid] and while it’s weird standing close to another person without a mask on, I do feel very lucky to have a job this year. I guess you just have to keep going when the world seems terrible. You have to hold on to some hope that more people are good than bad and things will get better.