Here in the dark cocoon of her parlour, Jennifer Coolidge comes alive. All day, the New Orleans heat made her leaden and itchy, but now that the sunlight has drained from the sky and the moisture has been wicked from the air, the actress is ready and alert. She asks me to fix us another round of tequila cocktails as she shuffles around her home in puffy pink slippers, closing doors and turning off lights to set the mood. She has been waiting for hours to unveil what she calls “the surprise.”

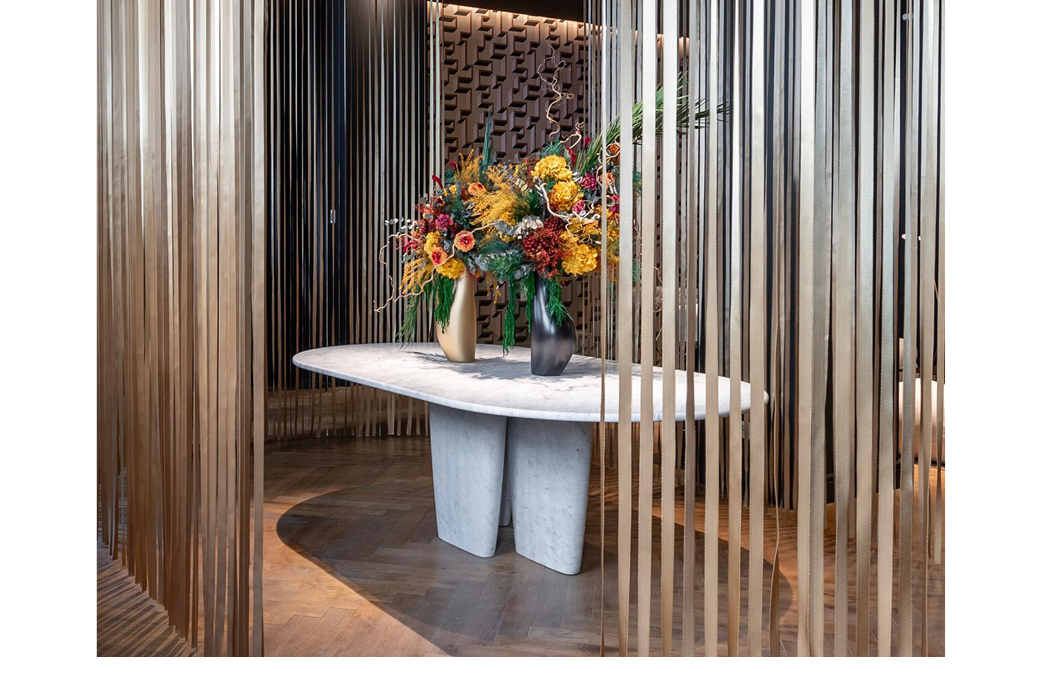

I arrived early in the afternoon at her home in the Lower Garden District, where she greeted me at the cast-iron gate, wearing a black slip and a sheer fuchsia-and-gold bolero, as her rescue dog, Chewy (short for Chewbacca), ran around the fluted Ionic columns. She bought this 1867 house just before Hurricane Katrina and has spent much of her time restoring it to its former Greek Revival–slash–Italianate glory: shoring up the foundation, replacing the wiring, repairing the roof, patching the plaster, and filling it with Persian rugs, tasselled ottomans, an upholstered minibar, armoires. Oil portraits in gilded frames stare down from the high walls. Coolidge believes there is a “presence” in the house, although not an evil one.

“Welcome to the mausoleum,” she announces as she emerges holding a candlestick with a clinking crystal skirt, a long black taper set inside it. She leads me into a darkened room with heavy drawn curtains and the smell of lilies in the air.

“Are you going to kill me?” I whisper.

“Yes,” she whispers. “I am.”

She lights the candle, and a wooden box comes into soft focus. She opens the lid outward, toward us, reaches inside, and pulls; a small, Asian-looking figure dressed in red silk emerges, maybe a hand and a half high, seated behind a tiny table. She tells me his name is Signor (she says it SEE-nyore) Blitz, a Parisian automaton from 1850 and a family heirloom. She winds a crank and Signor Blitz begins to perform legerdemain, lifting a set of cups and turning his head to the side in a mechanical loop. He opens his mouth to reveal a gleaming crescent of white and a slip of pink. When Coolidge was a little girl visiting her grandmother’s house, her father would show off Signor Blitz in the dark with a flashlight; she loved how the passage of time had both obscured and enhanced its magic. Signor Blitz holds a piece of her soul — and, maybe now, mine.

That Coolidge would live in a haunted house and be genuinely weird in a bone-deep way moves against the archetype she has played for almost three decades: that of the faddish, busty blonde of slow absorption. Known in the popular imagination as “Stifler’s Mom” from American Pie or Paulette the manicurist from Legally Blonde, her characters are sexy in a way that’s often deployed for cheap laughs — as in 2 Broke Girls, when the protagonists mistake her character, Sophie Kaczynski, for a madam. And yet even with just those bit parts, Coolidge has etched herself into the Mt. Rushmore of millennial camp, breathlessly copied and never quite replicated. Part of her uniqueness is her mien, her lips that pout like a scrunchie, her hooded eyes, but really it’s her voice and delivery that inspire delirium. The shortest lines — “Hi” or “Okay” or “So moist” — are putty in her hands. She stretches vowels out across entire emotional vistas: plaintive, alien, funny.

“She is her own comedic universe in or out of character,” says Eugene Levy, who has shared the screen with her in both the American Pie franchise and the films he co-wrote with Christopher Guest. “Jennifer is amazing at playing off of people,” says Guest, who first worked with her on 2000’s Best in Show. “And if there isn’t someone to play off, then she plays off the silence.” In that film, Coolidge is Sherri Ann Cabot, the proud owner of a blue-ribbon poodle and the much younger wife to an old man who never speaks. (They “both love soup.”) In For Your Consideration, from 2006, Coolidge is a daffy film producer. In a scene where other characters are fighting over creative direction, the real tension is in the way Coolidge’s eyes dart back and forth until she bursts out, “But what about me?!”

“I know that sometimes she gets frustrated that she’s always having hump-the-furniture parts,” says the TV writer and director Mike White, who became close friends with Coolidge after they met on a film set over a decade ago. “She can nail that kind of broad comedy, so of course that’s what people want her to do. People love her, but she’s put in a box.”

Coolidge finally got a more considered role in season one of HBO’s The White Lotus, an ensemble comedy of vacation manners White created about guests and the staff who serve them at a luxury resort in Hawaii. Acting alongside Connie Britton, Natasha Rothwell, Jake Lacy, and many others, Coolidge played Tanya, a wealthy middle-aged woman longing for affection and stability who goes to the resort to spread her mother’s ashes. “I was like, I would love to be able to write something that allows her to show the person that I know, not the ‘character,’ ” says White. The series taps into Coolidge’s comedic timing while capturing a sense of unpredictability and loneliness: Tanya is the most visibly distressed and distressing guest at the hotel, someone whose palpable need makes everyone else uncomfortable. [Coolidge has since reprised her role of Tanya to Emmy-award-winning acclaim in season two of The White Lotus].

Over a weekend with Coolidge, I learned to embrace unsteadiness. In person, she moves both slowly and chaotically, leaving you in a state of perpetual anticipation; it is just as unclear what will happen as when it will happen. Her natural speaking voice is more resonant, without the nasal breathiness she has become so associated with because of Legally Blonde. She loves to delay, riff, and sit with silence. She can talk, or not talk, for hours. And she loves a bit — although her eagerness to show me Signor Blitz is really a way to share something essential about herself. (She even named her production company after him.)

Sitting on the long velvet couch in her parlour, Coolidge thinks back to her parents. Her father worked in resin manufacturing and was a craftsman on the side, while her mother was a homemaker. “My father really worshipped my mother,” she remembers. “How did she get that? He really thought she was the most incredible person that ever lived on this planet.”

“What would you want right now?” I ask.

“What would I want?” she says, laughing. “In a dude or in love?”

“Or in general.”

“What would I want?” she pauses. “I don’t know. More tequila.”

Coolidge wishes she had a thicker skin or more gumption to just do the thing, like write a movie and star in it, the way Billy Bob Thornton did with Sling Blade. She grew up in Norwell, Massachusetts, and, when she was 21, moved to LA for acting school, where she lived in a rented room in a nursing home with another aspiring actor, the type who won bikini contests and bragged about it. “She was showing a photo of them, but then she said, ‘I just want to tell you something, Jennifer. I have a really good eye for talent. I don’t see you as someone in front of the camera,’ ” Coolidge says. Around the same time, a casting agent brought Coolidge in only to tell her she would never cast her in anything. “In your headshot, you look just like a young Candice Bergen,” she recalls the agent saying. “You look nothing like this. I only cast good-looking people on my soaps.”

She moved to New York and waitressed at Canastel’s at 19th and Park, where Sandra Bullock was a hostess. There were a lot of lost years when she was deep inside a coke habit. (“What a waste.”) When Coolidge went out to clubs like Area or Limelight, she pretended to be the least-known, completely fictional Hemingway daughter. “I always said I was Muffin Hemingway if I couldn’t get in,” she says. “One time I got thrown out of a club because I was behaving badly, and they said, ‘Don’t ever come back here, Muffin!’ ” Another time, she went to the Palladium and woke up the next day outside, near a tennis court in the Hamptons. Eventually, too many nights were ending in the ER. When she was 27, her parents sent her to rehab. When she got out, she found improv at Gotham City, which eventually led her back to LA to join the Groundlings, the comedy troupe that at the time included Will Ferrell, Cheri Oteri, Chris Kattan, and Chris Parnell. In 1993, at the age of 32, she booked her first big break — as one of Jerry Seinfeld’s girlfriends on Seinfeld — while her mother was dying of pancreatic cancer. “My mother’s last words to me were, like, ‘I can’t believe it,’ ” she remembers. “But she was thrilled because she didn’t think anything was going to happen.”

There is an always-the-bridesmaid quality to Coolidge’s career, of sliding doors and missed opportunities. The same day she got Seinfeld, she booked She TV, a short-lived sketch-comedy show that lasted for a brief season. After that, she was in Saturday Night Special, an SNL-rival attempt at Fox with Roseanne Barr and Kathy Griffin that again lasted one season. When Coolidge and some of the other Groundlings were sent to audition for the actual SNL, Coolidge’s (new) agent decided to play hardball and say the show couldn’t keep his client waiting for a decision — it was now or never. (SNL decided against now.) She says she played a shrink in an HBO pilot that didn’t get picked up. In 2003, as part of a development deal, NBC bought a half-hour comedy based on her time at Canastel’s but eventually passed on it too. In what was reported as a “consolation prize,” she played a horny agent on Matt LeBlanc’s Friends spin-off, Joey, which lasted two seasons. “It’s so funny when you’re on these shows and you plan your life; you think it’s all going to go so fabulous. And then two seconds later, it’s just through,” she says, laughing. “You’re like, Oh, really? It’s all over so soon?’ ”

Even The White Lotus, her richest role to date, is something of a runner-up. White — who created one of the canonical Best TV Shows You Missed, Enlightened with Laura Dern — had first conceived of a different star vehicle for Coolidge called Saint Patsy. It was going to be a “paranoid road comedy” in which she would play an underappreciated actress who gets a call that she’s receiving a lifetime-achievement award from an obscure film festival in Sri Lanka but spirals when she comes to believe the award is an elaborate ruse concocted by her ex-boyfriend in an attempt to kill her. “Honestly, it’s the best thing I’ve ever written,” White says. “If someone made this show, it would blow people’s minds. Just think of Jennifer getting bitten by a snake in the Indian Ocean and running for her life.”

He says HBO passed. “I got close on a couple places, but the craziness of it was too much,” White says. “People were like, ‘Jennifer as the linchpin to a show, as your way in …’ I could just sense there was some anxiety.” He blames the generally limited ability of network executives to see beyond the roles a person has already had, a sort of self-perpetuating mechanism. “Jennifer makes the comedy about herself. The joke is always on her,” he says. “It’s a disarming way of going through life — a way to put people at ease and try to defuse anything. You make yourself the joke, but what happens is that sometimes people then confuse her with being a joke.”

So when the network asked White to make a Covid-friendly show they could shoot in quarantine instead — what became The White Lotus — he insisted on including a meaty role for Coolidge. She was his nonnegotiable. “The same way people feel about her in Legally Blonde is how I feel about her in life,” he says. “I want to see her win.”

The day after I meet Signor Blitz, Coolidge texts me: “Hi Alex!! How are you feeling ?? I have an action packed evening I hope you’re up for it,” followed by alternating heart and prayer-hands emoji. She arrives at my hotel that evening in long lashes, a silk cheetah-print caftan, and crystal-encrusted heels that kick up her height (she’s five-foot-ten) even higher. In the front seat is William, an assistant at CAA whose provenance is a bit of a mystery. His little sister, a premed student, is driving and controlling the music, blasting Olivia Rodrigo’s Sour as we head to our first destination, Saint-Germain, a wine bar in the Bywater. “You got me fucked up in the head, boy / Never doubted myself so much,” sings Rodrigo. It’s Coolidge’s first time hearing the song. “I can relate to that,” she says.

We’re just here for some sips and apps, she tells Saint-Germain’s wine director as we step onto the patio outside. He remembers her preference for French whites, particularly Saint-Aubins. Coolidge loves to indulge, to go all out. Every year, she hosts a giant Halloween party, for which she removes the furniture from her house, places long tables in the double galleries, and treats the revellers to a catered meal, musicians, burlesque dancers, a costume contest, and endless wine. She usually tries to eat vegan, but it’s difficult on film sets or when there are so many delicious things, like aged Camembert butter and crab claws.

The server brings out a dish of thin coins of summer squash topped with crab and kaluga caviar and dots of bright-green lovage oil. That’s followed by the fanciest crudités I have ever seen, with cut-up vegetables dusted in puffed rice and buttermilk dressing. She asks if they have any bread; they don’t, but they do have some cornbread cakes that the kitchen makes to order. The cakes appear. She groans, I groan.

We discuss reincarnation. She grew up as a Unitarian Universalist, which ultimately means she believes in some big-picture thinker in the sky, although she’s not sure exactly what. Maybe God is gay. If she were to come back in another life, she would want to be a gay man. Why? “I don’t know,” she pauses. “I just … I think I’d be good at it.”

It’s impossible to overstate the mutual fixation between Jennifer Coolidge and gay men. They seek her out at parties, like moths to a disco ball, for photos and air kisses and conversation (and interviews). She wonders if this may be because she has “acted persecuted, in my own self-centered way.

“Whatever role they like, it’s something where they think I’m pretending to be a woman,” she says.

“That your characters are drag queens?” I ask.

“In some form,” she replies. “One time, this guy said it hadn’t occurred to them that there could be a woman like that until they saw A Cinderella Story” — a film in which she plays Hilary Duff’s evil stepmother, Fiona. “They said, ‘I realized you were me.’ ”

In turn, she projects a certain tenacity and put-togetherness onto gay men that she feels she may lack. Take William, she says: He grew up gay in a conservative part of Mississippi, yet here he is, capable, smart, thriving. She feels gay men are more generous than their heterosexual counterparts, more even than some women. “You’d think that a gay man would be condescending to me because I’m so not what they are. But I do feel gay men forgive me for it,” she says. “Gay men don’t make you pay for having a strong point of view. And I really like that because hetero men don’t like that.”

Coolidge is single and has never been married. She’s fascinated by liars and con men: The last time she had a Halloween party, in 2019, the costume prompt was to dress up as your favourite narcissist — or their victim; this year, she’s thinking it will be to come as your favourite fraud. These themes may or may not be inspired by personal experience. Either way, Coolidge stays in the game. She’s a romantic.

She doesn’t necessarily want to be dating some rich guy, but the more

salt-of-the-earth, non-Hollywood men she’s been with can be insecure

about her success. “Their perception of your life is so much bigger and better than what it really is,” she says. “They somehow project a bunch of shit onto you, that you’re usurping them or you’re doing something to them. You’re some sort of verb.

“I don’t want this to be the end of my life and my romance and all that,” she continues. “But I don’t know how people do it anymore. Sometimes I feel like you got this good little thing going once in a while with somebody. You get too much permission to, you know, be you. The thing dissolves pretty quick. There’s so many girls who would be like, Well, fuck them. They can’t handle it. But my feeling is, like, who wants to be alone, too?”

My last morning in New Orleans starts with a “coffee?” text from Coolidge. She takes us to one of her regular spots, Willa Jean, which leads to breakfast at Molly’s Rise and Shine, run by her friend Mason Hereford, who suggests she try the new vegan tamale. She insists on driving me to the airport and that, next time, I need to spend the night at her house. “I’ll stay across the street so you can really feel the creeps.”

Coolidge’s social anxiety feeds on wondering whether she’s doing enough for people or maybe doing too much. Hereford tells me that when he opened his restaurant, she came in and bought hundreds of dollars’ worth of gift cards. When she hired him to cater a party, she paid him double what he’d asked.

You think you really know yourself until you go through something and then you’re like, I had this all wrong.

“She’s very paranoid about hurting anyone’s feelings, about coming off as mean or entitled,” says White. He saw this in full force during a safari they went on together in Tanzania a few years ago; she wanted to tip the driver, then agonised over whether she had overtipped. “She did it with the animals, where she would be like, ‘Oh, there’s a leopard!’ And then she’d be like, ‘The leopard is looking at us weird.’ It would turn on a dime — she would go from loving the beauty of nature to projecting on this animal that they want to eat us and we’ve got to get the fuck out of there.”

The same fears apply to going after roles. She feels she has been passive about her career, that she took other people’s word — agents, executives, whatever — and assumed they knew better than she did. In the grand scheme of things, she knows she has a lot, and she’s not sure she really deserves it. Only when you compare her with other Hollywood actors do disparities in parts or pay start to arise. “So many people are just not making what they should be making. But I do think it is weird when someone just gets some massive amount of money and then other people who are just below them are getting one-hundredth of that,” she says. “If you’re called a character actress, it’s just an excuse not to pay you.”

Before the pandemic, she fantasized about leaving it all behind and moving to a house in the middle of nowhere. “Covid got rid of my dream to be isolated. No more dreams of living in a lighthouse,” she says. “I really figured out who I was. I need city life, city living. You think you really know yourself until you actually go through something and then you’re like, I had this all wrong.”

“Were there any other moments like that?” I ask.

She thinks for a second. “Either you’re too insecure and you think terrible things about yourself,” she starts, “or you overthink something great about yourself and then you have to have that realisation.

“I used to be a really, really fast runner, and I just assumed I still was. And then I did a movie recently, Shotgun Wedding, where you had to run really fast. You’re screaming, and you’re running. This fantasy I had about myself, I thought I was an Olympic athlete, you know? Then you’re just like, Holy shit,” she says. “It was a humbling moment.”