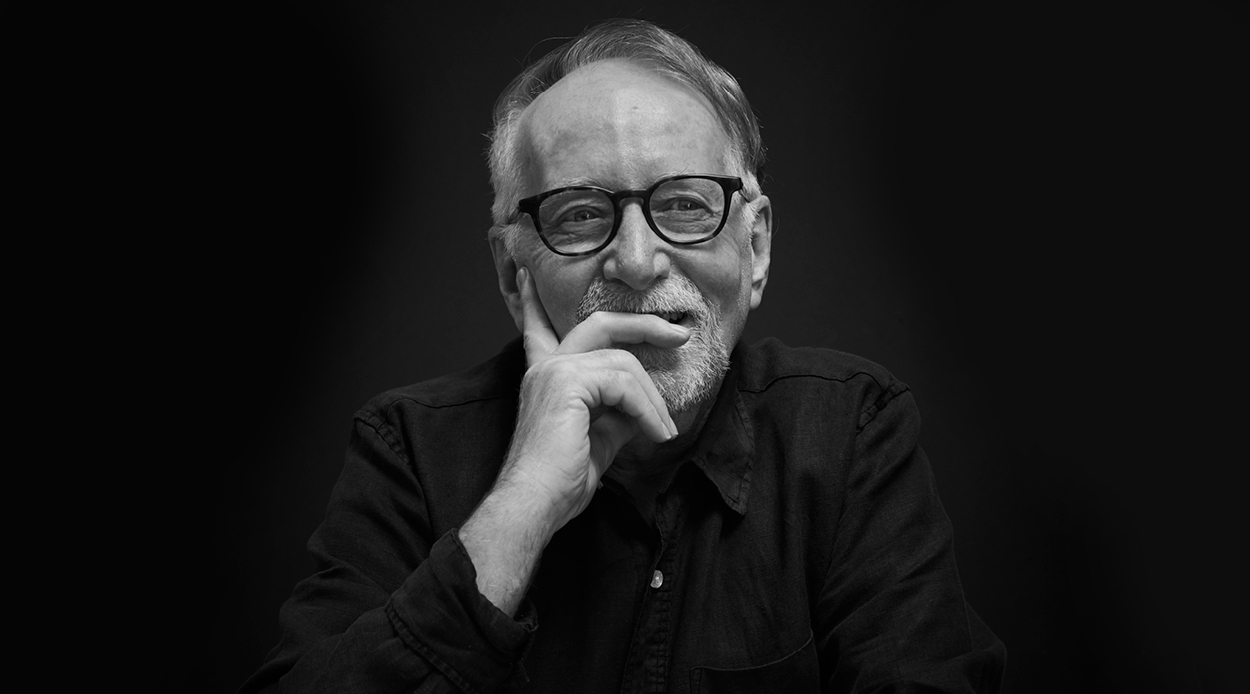

His eponymous Parnell restaurant, Antoine’s, shut its storied villa doors in December last year after 48 years of operation. One of the hospitality industry’s longest-standing and highly respected stalwarts, Tony Astle sits down with Sophie Gilmour for a lesson in career fulfilment.

I met Tony Astle for lunch at a Japanese restaurant in Parnell. I notice the moment I arrived that he looks well — perky, relaxed and sipping on a glass of rosé. I conclude subconsciously that it’s because he’s ‘out of the game’ now. Although it may be true that the hospitality game is wearing many a restaurateur (myself included) thin at the moment, this millennial was in for an unexpected lesson in “constant gratification”. A distinctly different kind to the instant version my generation has become addicted to.

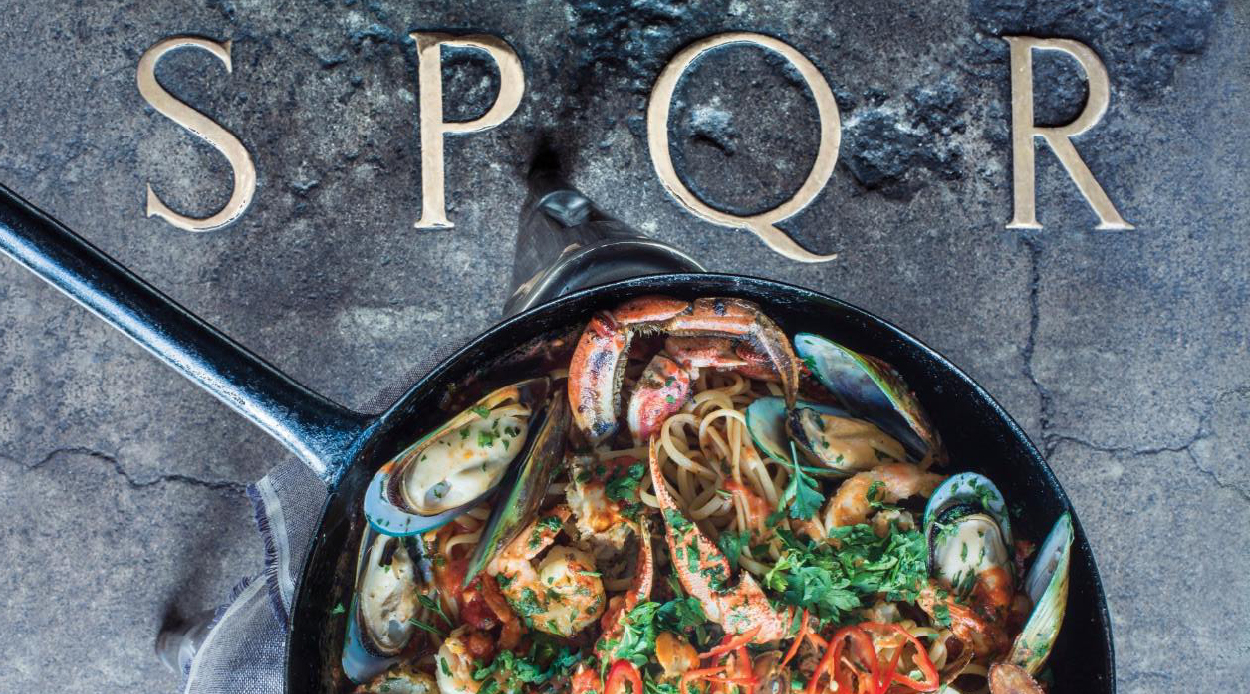

I asked Tony to take me back to the origin story of Auckland’s beloved Antoine’s, the fine-dining French restaurant that he and his wife Beth owned and operated in Parnell for 48 years — until December 2020. I remember my parents taking my sister and I there for a special occasion as young girls, and that it felt like a visit to an ivory palace with silver service, waistcoats and liquorice ice cream. My sister cried when my father cracked her crème brulée before she had the chance.

Tony tells me he worked at The Coachman in Wellington in 1968 before moving back to his hometown of Christchurch, where he bought a dairy. Beth, who was a hairdresser at the time, worked in the dairy at the weekends. Together they moved back to Wellington where Tony restarted at The Coachman. They fell in love and were inspired by Des and Lorraine Britten [The Coachman owners] to open their own restaurant together.

Tony had loved his chosen career since he was 15 years old and said he knew that his own restaurant had to be fine dining, silver service, and upmarket. He assures me that although his ideas all sounded “rather pretentious”, Beth was the calming and practical influence. Their initial plan was to operate for a five-year stint and then reassess whether to have a family or to travel the world.

I love eating with food people, Tony orders a delicious lunch. Prawn custard and tempura vegetables with grilled eel. The conversation flowed. I’ve known Tony my whole life, but hardly seen him for 25 years. He owned a restaurant with my mother called Tatler in the early 90s in Galway Street in what is now Britomart.

I’m familiar with his reputation for being a straight-talking, politically controversial, sometimes hot-headed character and I’m always up for a bit of healthy debate. I’m also aware that he recently lost his beloved wife Beth to cancer — he’s been in my thoughts. We discussed the good times, the bad times, sickness and health — but on reflection, the most marked takeaway from our conversation was that Tony and Beth managed to be consistently fulfilled by their restaurant for all its 48 years.

To be honest, I’m shocked. I rolled up to lunch five minutes late straight from the shop floor at my beloved Fatima’s, feeling a little disenchanted with the operational burden of running a hospitality business in 2021; the relentless putting out of fires, the desperate struggle for staff in an uncertain market, the daily roster-shuffling to accommodate sickness in our 40-strong team. Tony doesn’t share this sentiment, and it served me a strong shot of perspective. We agree it won’t be like this forever. “There was no best year…. most years were great”, Tony tells me. Apart from 1989 – 1993 that is.

Tony said with effortless certainty that he always felt blessed to have found and continued “a career that was so enjoyable, a true pleasure to be involved in and to go to most days”. He speaks of the many incredible people he has met and served along the way.

This comes up several times. It strikes me what an enormous appreciation for his customers Tony has, as he takes time to tell me what good people many of them were. Many stood by him during the pandemic’s infancy last year and he feels grateful for that. It also struck me how hard he and Beth worked — six days per week, 6am to 2am, for 48 years! Tony would start later than Beth and she finished before him. Beth would start by cleaning the whole restaurant herself each day, Tony popped home for a nap mid-afternoon to prepare him for the late finish. What immense pride they had in their work, I think to myself.

Tony fits the stereotype of an old-school chef in some ways. He has always been a fan of a late-night hoolie and he reminds me that some things don’t change. In other ways though, he is the exception to the rule. Tony and Beth managed to create an extraordinary life for themselves outside of the restaurant. They closed the restaurant for five weeks in the middle of each year and three weeks each Christmas. They prioritised annual international travel to experience the best restaurants and hotels in the world, clocking many people’s bucket lists, with trips on the Concorde, the Oriental Express and the QEII. Tony cooked on their travels as well, taking Antoine’s on one or two-week stints to the Hilton in Singapore or The Western in Japan or Thailand.

It’s gratifying hearing the rewards they reaped for all their hard work. They deserved it. In what I can only presume was a crude attempt to make myself feel better mid-pandemic, I ask Tony to take me back to the stock market crash, the only tricky era he has mentioned.

Tony tells me that “by 1990 everything had fallen over”. Although the stock market crash had been a couple of years earlier, it took until 1990 for the effects to hit the restaurant and 50 percent of Antoine’s’ turnover disappeared. The high flyers vanished and the cars outside Antoine’s went from very upmarket to a lot of “run-of-the-mill Toyota types”. The lunch trade, which had formerly been buzzing with advertising types and property developers, reduced to almost nil. Tony and Beth reduced their staff roll from ten to just four, including themselves. They requested and received a rent reduction and banked on their long term loyal customers to support them — and they did. I am reminded of my own relentless optimism, and I’m grateful for it at this moment.

Tony puts their survival of this period down in part to being owner-operators. It took he and Beth three years to revive the business, although lunches were never big again. He said it felt like starting over again, but this time reality had finally set in and they knew how to run the business. I learned this lesson the hard way too, as we sip our rosé and agree that there is nothing like being cash flow negative to school you on how to operate profitably. Tony and Beth never returned to ten staff, opting to run with five until last year. We discuss the challenges our industry is facing now — increasing compliance, the rising need for marketing spend, the chronic shortage of staff, the lack of resources to train them, the vanishing margins. I’m intrigued to hear what he thinks the solution is, the question on so many of our passionate comrades’ minds.

“It’s a cut-throat business… there are too many restaurants and not enough trained staff or in fact, not enough young ones wanting to work”. He has little patience for the young generation blaming low wages for not dedicating themselves to the hospitality industry. “Blame attitude”, he says… “if you are good, wages follow… walk before you run”. I’m currently refusing to participate in a price war as our industry competes for every fresh hire in Auckland, and in that moment I feel so seen. I sit with Tony’s initial comment for a moment and I wonder why we’re being fed the ‘everything now’ mandate, and whom it serves. The journey is what has given Tony the most satisfaction and fulfilment, not the destination.

I ask Tony if he knows what his next ‘destination’ is and he dismisses the notion of retirement wholeheartedly. Tony has been asked to participate in AUT’s culinary department and has an idea about producing exquisite ‘ready meals’. Demand for his tripe and oxtail and duck hasn’t waned since Antoine’s closed its doors and he has been cooking at home for catering orders he just can’t help but fulfil.

As we finish our second glass of rosé, I remember, regretfully, that I’m due back at work. I feel compelled to ask Tony’s advice for young and passionate restaurateurs today. “Own your own restaurant and work in it. You are the restaurant. Don’t think hospitality is a way to fame and fortune… work hard”.

I push back on this, on the basis that the stakes have never been higher owning your own restaurant in New Zealand. We discuss risk and reward in the context of multiplying construction costs, over saturation of restaurants and high rents, and Tony takes a financially conservative line. “Don’t over-capitalise. Be in control. Make sure you have done a business model. Know the tax laws. Be aware that health and safety and employment laws can be a nightmare. Due diligence is imperative. Remember that every staff member employed is money off the bottom line”. I am compelled to print these words on my consultancy’s homepage!

Does Tony have any regrets? “Not too many” he pauses… “I thought I’d have another 20 years with my wife after Antoine’s… but we had 53 years together. I feel lucky to have travelled to so many amazing places with her over our 48 years at Antoine’s. Beth would have liked one or two children, but it wasn’t to be”.

In their place, many of their wonderful staff became and remain their family. I’m wondering whether his penchant for French food extends to France when he says “Oh, I would have loved to go and live in the south-west of France about 15 years ago. Maybe that can still happen, but it won’t be the same without my long-term friend and partner”. I’m so moved by what’s still most important to him after all these years.

The final curtain on Antoine’s came on the 18th of December, 2020 and Tony described it as “the worst feeling ever”. I tell him I remember feeling physically sick the day we sold Bird On A Wire. Beth was ill and needed his full attention. She had given him 50 years of full support, and it was now Tony’s turn. He and his best friend Simon Woolley (Tony’s “saviour throughout this very difficult period”) decided together on the 14th of December to close the doors without any fanfare on the 18th. Tony describes a van arriving the next week and stripping 48 years of life away. Tony paused and then said, “I think I am still numb”.

Forty-eight years is an extraordinary tenure for an Auckland restaurant, one that Tony and Beth felt rightfully proud of. I feel connected to Tony’s bond with his restaurant, the rose-tinted lenses that carried him through the toughest times and how visceral the end of the era felt. I feel boosted and treated to the perspective of someone who has done the hard yards and I stand in admiration of the bond he and Beth shared whilst achieving all that they did.

Auckland misses Antoine’s, and its customers miss Beth. Tony’s work here is not done though, there is much to look forward to.