Thanks to the omnipresence of the online world, what our childhood looked like is far from comparable to that of children today. The future of the world has reached a tipping point, where our children’s physical and mental development and health are being impacted beyond repair. Following in the footsteps of other countries, a groundswell of prominent New Zealand business leaders has formed B416, a charity-led initiative intent on getting a government-mandated restriction on all social media access to anyone under 16.

Still in their pivotal years of development, under-16s are not yet equipped to fully recognise the pitfalls of social media — and it’s our responsibility as parents to protect them. While autonomy and a sense of agency are essential for growing minds, the complexities and risks of the online world are far beyond what most children can reasonably comprehend. Parents do their best to monitor and manage usage, but the truth is, meaningful change must happen at a systemic level — and it must happen now.

Sign the petition here.

A quiet but perilous shift is happening in children’s bedrooms nationwide. At first glance, they might seem tidy, even serene — minimalist white walls, a few possessions scattered across the floor, a school bag slouched in the corner. But look closer, and that simplicity carries a frightening weight. There’s no life on the walls, no evidence of play or passion. One perturbed mother recently told researcher and public health advocate Dr. Samantha Marsh, “[My daughter’s bedroom] is like a cell. There’s nothing on the walls. No posters, no photos, no books lying around. None of her personality is in that room — because her whole life is on her phone.”

Welcome to childhood in the age of the algorithm.

The B416 initiative — a growing movement advocating for children under the age of 16 to be shielded from social media — isn’t a reactionary moral panic. It’s a call for some semblance of calm in a storm of overstimulation — a safeguard to preserve what is precious. It’s founded not in fear but care, backed by research, lived experience, and the sobering weight of countless stories from the frontlines.

And few have walked that frontline more intimately than Jo Robertson. Robertson’s work spans a decade in sexual health education, trauma therapy, and child advocacy. Her stories are not abstract statistics — they’re first-hand, tangible tales, centred on children in New Zealand. “I’ve worked in trauma, usually sexual trauma, with children and young people in primary schools, intermediate, and high schools,” she shared. “Some of the stories that were coming through my office doors involved children who were only six or seven replicating sexual acts they’d seen online with their friends, or sometimes even with their siblings.”

This historic marker of risk, signs that once pointed to issues within the home, no longer tells the same tale. “My supervisor actually said at the time… we used to see this as a sign of abuse in the home, and we don’t see that anymore. We now see it as a direct sign of activity online.”

Another story she tells involves a 10-year-old girl invited to a playdate that turned into something else entirely, “They made out to be kind to her, offered to do her hair and makeup, only to make her look terrible and laugh at her. While she was washing the makeup off in the shower, two girls came into the bathroom and took videos of her.”

It’s the kind of cruelty that, in another time, might have been confined to a schoolyard. But today, “that story ends one of two ways, based wholly on whether those kids have access to social media.” If they do, Robertson explains, “those 11-year-old girls can upload those videos of a naked 10-year-old onto Instagram, onto Snapchat, onto TikTok.” The digital ecosystem, she notes, doesn’t just amplify harm. It immortalises it, allowing those intimate photos to be viewed forevermore by anyone across the globe.

“Social media acts as an accelerant. It’s like throwing fuel onto a fire,” says Robertson. “It changes scope and duration. It can last for a long time — forever.” In a world where platforms profit from engagement, no matter how exploitative the content, the risks are not just emotional but systemic. Robertson has worked tirelessly through organisations like The Light Project and Makes Sense to push for regulatory change. But years of conversations with politicians have left her frustrated and no further ahead. “I ask the same question every single time: When will you intervene? Nothing has changed in eight years.” In fact, Robertson says, we’re worse off now than before — previous safeguards rolled back, potential protections shelved, while children’s exposure and vulnerability continue to rise.

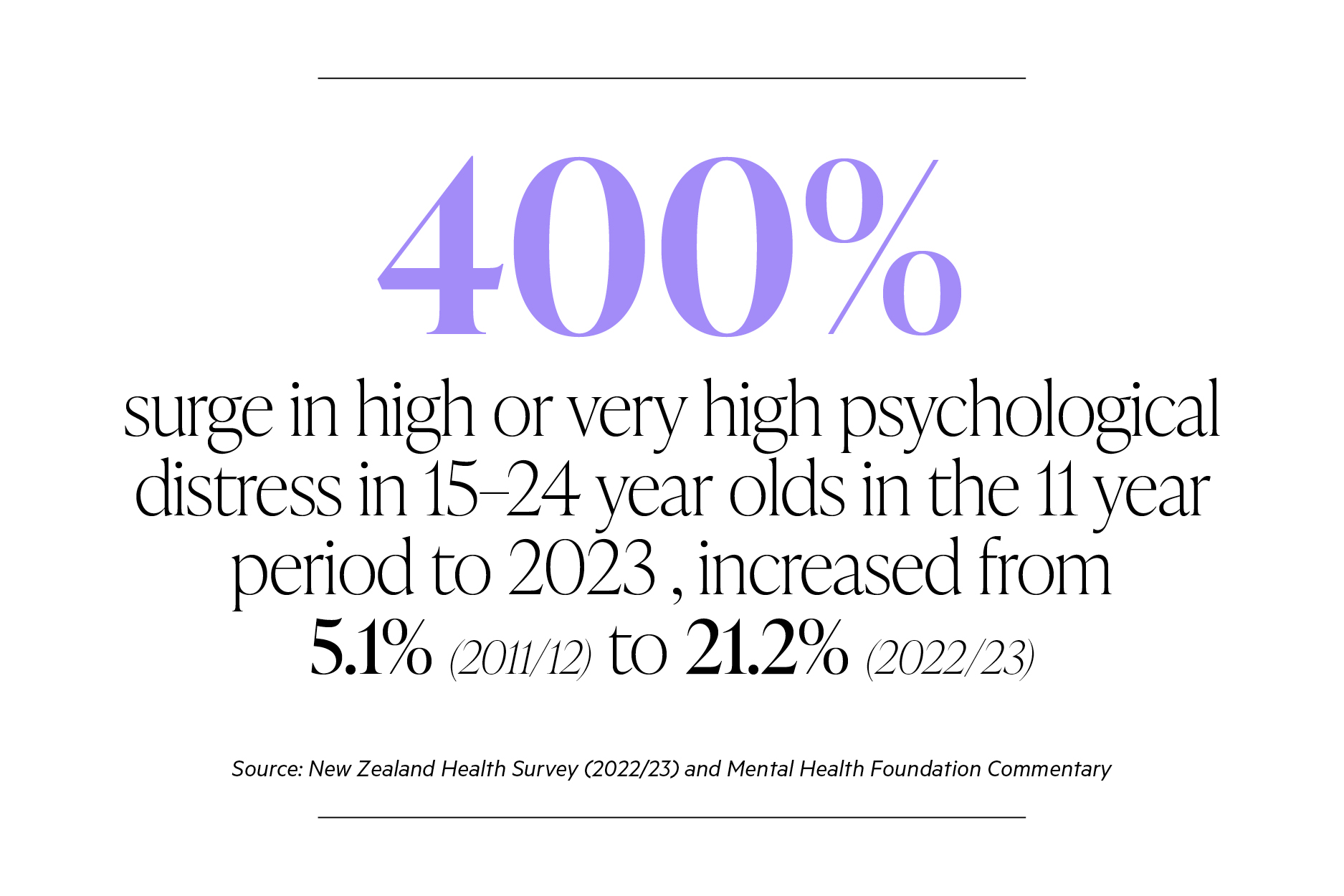

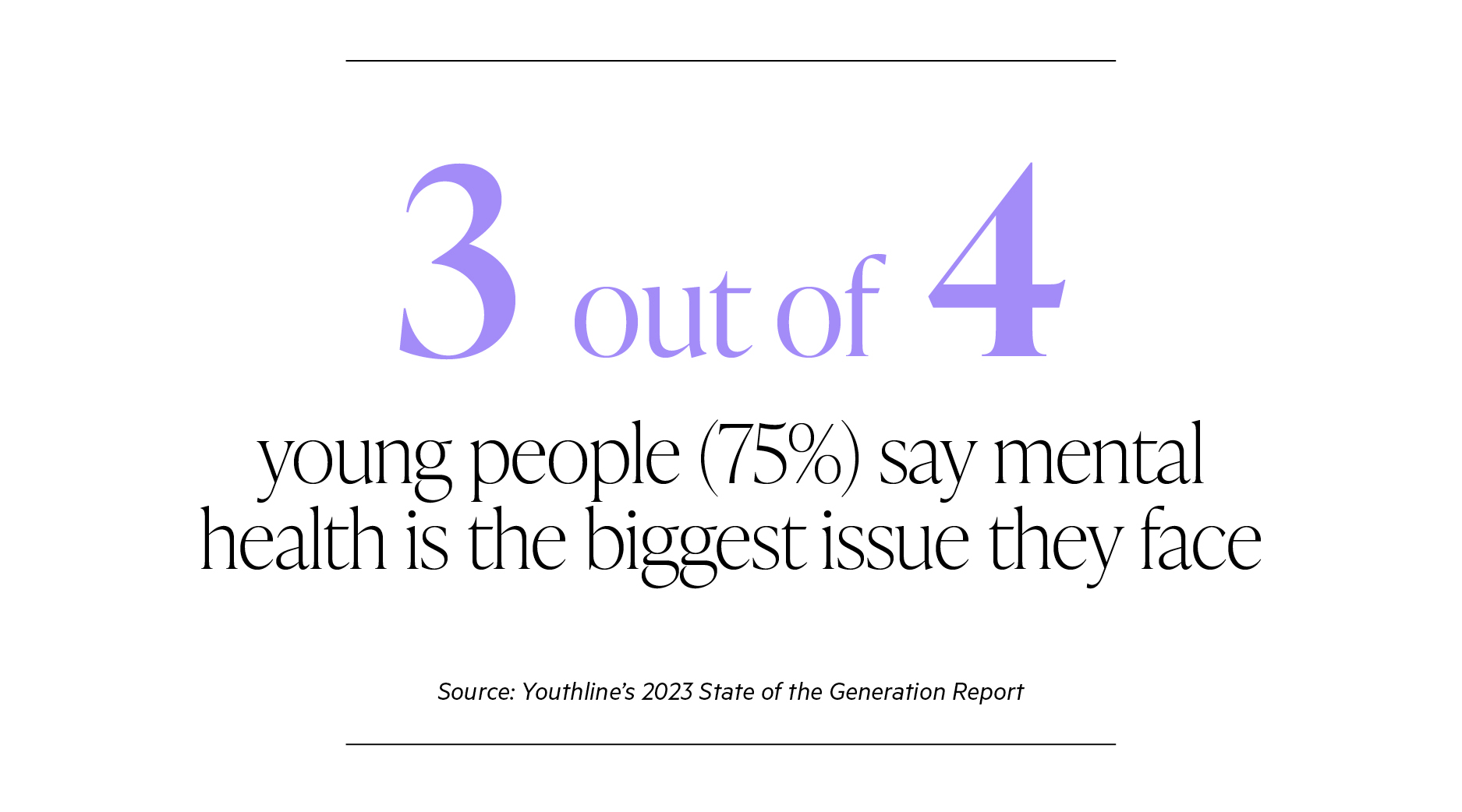

Another of B416’s figureheads, Dr. Samantha Marsh, brings the research lens to what Robertson witnesses on the ground. A senior research fellow with a background in child and youth wellbeing, Marsh underscores the magnitude of the issue, not just in terms of what children see but what they’re missing out on. “There are some irreducible needs of children that must be met for ideal development,” Marsh explains. “These are things like face-to-face time with peers, a strong parent-child relationship, time alone with their thoughts and ideas, sleep, and time in nature.” All of these, she says, are being displaced by smartphones and social media. Her concern is not just about predators or inappropriate content, though, as she points out, those dangers are all too real. Marsh is focused on the broader ecosystem. “Social media has changed the environment in which our kids are developing, and the way in which our kids’ brains are developing.”

She continues, “Our kids only have one brain and one childhood in which to develop that brain. And parents, schools, healthcare providers, and policymakers must do everything they can to ensure that the social environment our kids are exposed to is conducive to ideal development.”

The problem is far too enormous for children themselves to solve. They are, after all, only children. Part of the power of B416 lies in the clarity of its premise. The problem is not that children aren’t navigating the internet wisely; it’s that they were never meant to. As Marsh puts it, “These platforms are designed to hijack the reward systems in our kids’ brains and hold their attention for as long as possible. Our kids don’t stand a chance. That is why this isn’t their problem — it’s ours.”

Robertson echoes this truth in one of the most troubling stories she tells — that of a 14-year-old boy who approached her after a school talk. He said in a whisper, “I think about hurting girls.” She asked him why he thought that was okay, and he replied, “I think it comes from what I’ve seen online.” According to Robertson, that is not a boy who wants to hurt girls. That’s a boy who’s been so profoundly influenced by the content that’s been fed to him from an algorithm, that he now can’t separate his thoughts from those being forced upon him.

“Currently in NZ, we are allowing companies to profit off our kids’ attention at the expense of their physical and mental health,” Marsh said. “Within a recent report commissioned by the President of France, he stated: ‘What makes a nation rich is its youth, and ours is not for sale.’” New Zealand’s youth, too, should not be for sale, and action is desperately needed.

B416 isn’t a rejection of technology. It’s a safeguard — a reclamation of childhood. A movement for policy, not platitudes. And a stand, ultimately, for something as simple and essential as time — time to grow, play, connect, and mature.

As Robertson puts it: “We can change this. If we don’t force change, another generation will be in exactly the same position, if not worse.” It’s on us to protect our children from harm and give them back the irreplaceable: a childhood.

Sign the petition here.