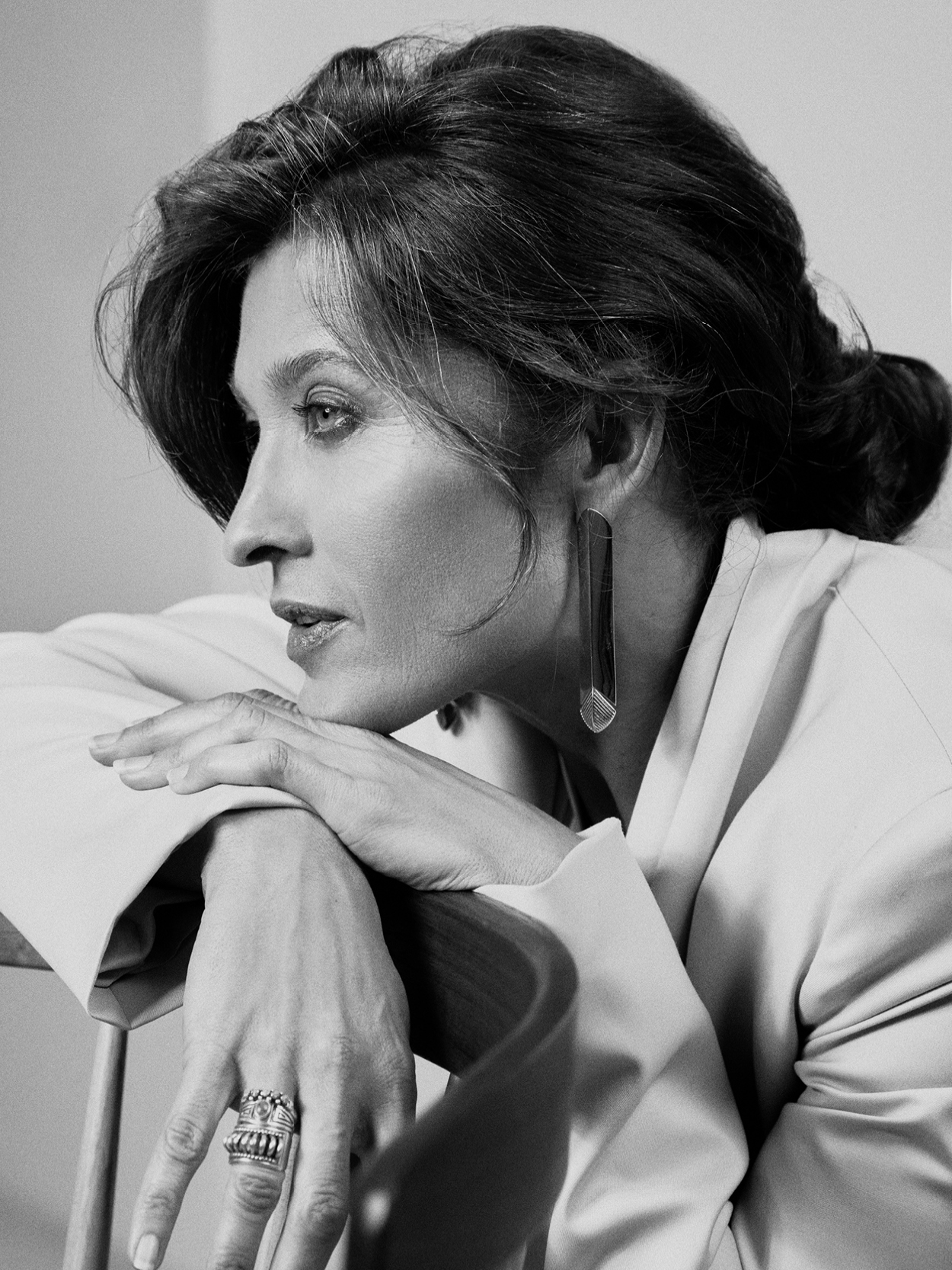

For anyone watching, it would seem Chelsea Winstanley (Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi) has reached the apex of a successful career in film. However, the Academy Award-nominated filmmaker will happily tell you she’s still on a journey to discover what this looks like, both for herself and for the stories she wishes to champion. With an impressive amount of projects on the go and in the works, Winstanley’s storytelling prowess is as multi-faceted as the woman herself, and her formidable drive means that, whether pitching to Hollywood executives or putting her all into independent projects, she is a force to be reckoned with.

Raised in Mount Maunganui, Winstanley’s entry into film came “probably later than most”, but after majoring in film production at AUT and graduating top of her class with a Media Peace award for her first-ever documentary, even juggling single motherhood as a 23-year-old, Winstanley shone. Now, with nearly 20 years’ experience as a writer, producer and director, she is one of Aotearoa’s foremost trailblazers in the industry, with a unique and assured point of view that she wields with beauty, courage and sensitivity.

In 2014, she co-produced hit vampire mockumentary What We Do in the Shadows with her former partner Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement (it became that year’s highest-grossing local film), and was the sole producer on acclaimed documentary Merata: How Mum Decolonised The Screen, which was picked up for distribution by famed US filmmaker Ava DuVernay. Winstanley became the first indigenous woman to be nominated for a Best Picture Academy Award after producing Jojo Rabbit and, this year, was recognised as a Kea World Class New Zealand Award winner.

With a passion for story sovereignty among indigenous peoples — particularly Māori women — Winstanley has dedicated herself to furthering these voices in the stories she tells. With her global outlook and connections, she is bringing Māori and indigenous voices to the world. Early in 2020, Winstanley founded production company This Too Shall Pass, under which she is currently working on a documentary feature film about the landmark Toi Tū Toi Ora exhibition that showed at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, earlier this year.

Coming up, she and co-producer Tweedie Waititi have secured the rights to dub and release two more Disney films — (you may have heard of them, The Lion King and Frozen) — in te reo Māori, following the success of the te reo version of Moana. Here, Winstanley reflects on her journey thus far and shares her thoughts on the industry, her process, motherhood and overcoming imposter syndrome.

When I was young I had an imaginary friend called Kak. She was so real to me. I would make my dad set a place for her at the dinner table, insist the front door be left open until she came inside, and I would squeeze into the middle of the back seat of the car so she could sit next to the window. My siblings thought I was crazy and I guess my parents put up with it. The significance of her existence became more apparent to me as an adult, when I started to delve into my past. When I was around seven and my parents split up, Kak and I would sit in the lounge after school, surrounded by every large object from the kitchen drawer — the place where the sharpest knives are kept. Everything we could muster, from the heavy sword-like knife sharpener, the egg slice, the carving fork… anything we could get our hands on. We sat there, on edge, waiting for dad to get home from work. She was my protector, my best friend and one day she disappeared. I’ve written a short film about her that I hope to make one day.

My passion for film first came about when I saw the merging of still and moving images in the documentary Bastion Point: Day 507 by Merata Mita. I had always been interested in photography and had not seen it used in such a creative way in storytelling before. There was something so arresting about it that made me think about film in a different way. Although I had seen movies at the cinema when I was young, my childhood was rooted in the beach at Mount Maunganui so I wasn’t immersed in cinema or living near a city that had a film festival, so my discovery was probably later than most.

The journey to where I am now has involved a lot of self-belief. When I started in this industry I had put myself through university as a 23-year-old solo mum of a two-year-old baby boy. I had an intrinsic belief that education was the only way for me to get out of the situation I was in, which at the time was a statistic. By all accounts I was a young Māori mother on the benefit with no prospects, but something inside of me knew this wasn’t it. Merata Mita once said, “when you have children, you have an investment in the future”.

I wanted my son to see me achieving and contributing to making the world more empathetic, more understanding and more tolerant, and storytelling was a way to do that. Taking the time to listen to someone else’s journey can be life-changing. I wanted my son to see that no matter what happens in life, you have a choice and to not be held hostage by your past. Accept, acknowledge and move forward. Allow your past to motivate you, not define you.

After university, my first job was at Kiwa Productions, a TV production company owned and operated by two wāhine Māori, Rhonda Kite and Libby Hakaraia. It was thrilling and exciting to be working with women I admired and who are still, to this day, making transformational changes for Māori participation in storytelling. I had made a short documentary for my final year at university, based on my cousins at my marae, Paparoa, who were running a tourism venture while also holding down full-time study. What they were doing was finding a way to transfer traditional knowledge to the next generation, while keeping the ahi kā (home fires) burning. I was in awe of my cousins and I wanted to celebrate them. I called that film Whakangahau (to celebrate/entertain) and I won a Media Peace Award for it. It was the affirmation I needed and I’m grateful because it said to me, in that moment, the path I had chosen was right.

I’m into shining a light on the positive in everything I try to do.

The stories I like to tell are based on celebrating and highlighting the beauty that is Māori. Simply for the fact that, despite the imperialistic pursuits of Britain and the subsequent devastating effects of colonisation, Māori are still here and we are thriving. Our love for the whenua and for one another are values every single person living in Aotearoa can live by. It is only fear of the unknown that inhibits our growth together as a nation.

We are so excited to have secured a further two Disney titles to dub, especially after the Moana reo Māori was so successful. The Lion King gives us a really good opportunity to be quite pan-tribal, and delve into different dialects from different iwi.

For us, first and foremost, it’s about being able to normalise te reo Māori. Disney is such a well-known product — we all know it as a brand and also one that is family-orientated. Because it can reach both Māori and Pākehā, it’s almost like an ‘in’ for people, you know how sometimes people feel a bit afraid to give Māori a go, or think that because they’re not [Māori] that they can’t, but it’s just not true. We all live here in this country,

we should all be able to feel like we can have these languages.

The cool thing about The Lion King is it spans so many generations. The themes of morals and looking after the land and one another, are universal themes. We’re really excited that Disney is taking us seriously and that comes down to what Tweedie [Waititi] and her team delivered the first time with Moana.

A goal I have that I’m yet to realise is to korero te reo Māori fluently.

I’d like to be known for being part of a movement that was dedicated to equitable participation in storytelling.

People would be surprised to know that I am named after a Black American singer. Her name was Chelsea Brown. My mother named me after this singer but most people associate Chelsea with England and football — I don’t particularly like either.

My working process is intention first, the ‘how-to’ comes later. When I first started directing and telling stories, I was just fascinated with people and I was genuinely interested in other people’s journeys.

The best piece of advice I’ve ever received is “this too shall pass”.

I believe the fundamental factors to keep in mind when making a film are to ask yourself questions all the time. What is my intention? Am I the right person to tell this story? Will this story add to my spiritual growth?

Something I would like to see more of in the film industry is women at the table in every facet of the pipeline of filmmaking — from producing through to distribution. They don’t exist without each other and right now we do not (in Aotearoa) hold a position in distribution. I want to change that.

One of the most impactful cinema experiences I’ve had was going to watch Stop Making Sense, the Talking Heads documentary by Jonathan Demme. I loved it because I got to sneak in with my sister, who’s six years older than me. I remember watching her and her mates dancing in the aisles.

The most important lesson that life has taught me is “find the courage to stand up for yourself then stand up for someone else” — a quote from the formidable, late Dr Maya Angelou. I don’t believe in the singular or individual pursuit. We are stronger in numbers, we have to be. United we stand, divided we fall. It’s a classic imperialist colonial view to be an individual and it doesn’t work. Throughout history we have seen it played over and over again, and we see it now, with everything that is happening in the world from the current pandemic to mass migration due to famine, war and genocide to basic human rights. Most of the decisions that have led to the atrocities perpetrated by the human race have been made by men. It’s time to hand over the power. We would be better off if women were in charge.

Being a mother has taught me the hardest lessons in life but for that I am grateful. Compassion, love, empathy, selflessness, hard work, heartache and failure. Parenting is the hardest job ever. You have to constantly accept that the decisions you make were, or are, the best you could at the time, for the circumstance you were in. Upon reflection they might not be the best decision but you have to forgive yourself and know it is all part of your spiritual growth. As parents we need to be kinder to ourselves and to be in constant communication with our children about this. I have made some terrible choices but as Dr Angelou says, “do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.” I love a good quote!

I perform at my best when my intention is in alignment with my soul’s purpose. It might be weird to say that, at 45, I’m just realising what that is. I really feel like I’m coming into my own, I’m more confident, and more confident to say I’m a storyteller.

The rules are meant to be reimagined.

I would love to collaborate with many people. One is Ripeka Evans, on a story about the women involved in the anti-apartheid Springbok tour movement in the early 1980’s.

I really admire people who, despite what life throws at them, get up and keep going.

While I try not to be too angry these days, I am disappointed that the entitled and privileged in Aotearoa continue to ignore the fact that their intergenerational wealth is accumulated off the back of stolen land and dispossession of Māori.

My definition of success is freedom. Freedom from self-limitation. The freedom that comes from saying yes, and not being afraid.

I’m most proud of the film Merata: How Mum Decolonised the Screen. It was an honour to work with her son Hepi. I learnt so much about her that I didn’t know. To have Ava DuVernay distribute it was my most proud moment as a producer. I love her fearless approach to participation in the pipeline of storytelling. She is a champion for women, people of colour and groups who have been traditionally left out of the storytelling process. Without her support, the film would not have been seen throughout the world.

The personality traits that have contributed to my success are self-belief, tenacity, happiness, gratitude and gut instinct.

The future for me looks incredible. I am moving into spaces of the film pipeline that we have never occupied before. I am more confident in my choices as a director, writer and producer. I feel incredibly grateful but most of all, free.

Home is transient. I am happy to be living in Tāmaki Makaurau for now, my heart will always be in Tauranga Moana, and I look forward to the time we can travel again and see the world.

Something I want to instil in my children is a love for their culture and language and for them to know they have nothing to fear except fear itself.

The biggest thing I’ve had to overcome is imposter syndrome. When I was a child, I was not taught that I could belong anywhere I wanted to, so I have spent a long time trying to prove that point. I don’t, so much, anymore and I am not sure if that comes down to confidence, age or just not paying attention to that nagging voice anymore. I am enough, I’m enough for me.

I will say this: I accept that I am a work in progress and that life is a soul journey — right now I am just doing the best I can.

Image credit: Makeup: Phoebe Watt