In the world of contemporary design, where form often wrestles with function and innovation must be tempered by purpose, Karim Rashid has forged a career that transcends aesthetics. His work, spanning decades and disciplines, reflects a philosophy rooted in sensual minimalism — an approach that champions warmth, humanity, and the intrinsic beauty of everyday objects. But beyond the striking silhouettes and thoughtful functionality of his designs lies a deeply personal journey, one shaped by an eclectic upbringing, a lifelong pursuit of excellence, and an unwavering belief in the power of design to shape the future. Here, we catch up with the designer ahead of his address at Auckland Design Week.

From Cairo to Rome, Paris to London, and eventually across the Atlantic to Canada, Karim Rashid’s early years were shaped by a constant state of movement — a life lived across cultures, continents, and artistic landscapes. Born in 1960 to an Egyptian father and a British mother, he was immersed in a world where creativity was innate. His father, a designer for Egyptian television and later a collaborator with Cinecittà in Rome, fostered an environment rich in artistic expression. Pencils, markers, and paper were always within reach, and the act of creating became as natural as breathing, “We were brought up in an extremely inspiring context that gave me great respect for all of the arts,” Rashid muses.

Despite this creative upbringing, the path to design was not always a clear choice. As a teenager, he grappled with indecision, struggling to decide whether to pursue architecture, fine arts, or fashion. His future seemed spread across multiple disciplines. When he applied to Carleton University at just 16, the architectural program was already full, steering him instead towards industrial design. Fate, as it turned out, had intervened. It was there, amidst engineering, philosophy, and design courses, that he found his true calling: shaping the objects that define our everyday lives.

His education was more than just training in design — it was an immersion in broader intellectual pursuits. Studying in a program that had yet to establish rigid boundaries, Rashid explored everything from engineering to architecture, philosophy to language. It was this holistic approach that laid the foundation for his distinctive design sensibility — one rooted not just in aesthetics but in function, human behaviour, and emotional connection.

“Every object in our lives has the potential to inspire… But they must work. Good design is about solving problems, not just creating beautiful things.”

After graduating, Rashid made for the home of design — Italy. A one-year graduate program placed him under the tutelage of two design luminaries: Gaetano Pesce and Ettore Sottsass. Sottsass’s architecture group, Memphis, with its bold, humanistic design ethos, proved a revelation to Rashid. Sottsass, in particular, imparted a lesson that would stay with him: “There are many beautiful design objects, but you have to ask — what do they do for us? What is left, if you take the design away?” That question would become the guiding principle of his career.

For Rashid, inspiration is an intuitive process — one shaped by years of observation, interaction, and immersion in the minutiae of daily life. He looks to the everyday, seeking to elevate the seemingly banal into something poetic and functional. “Every object in our lives has the potential to inspire,” he muses. “But they must work. Good design is about solving problems, not just creating beautiful things.”

This belief has carried through his extensive body of work, which spans furniture, interiors, product design, and brand collaborations. Whether it’s the Alessi Kaj, a soft and sensual yet practical timepiece, or the Cadmo lamp for Artemide, a sculptural embodiment of light and shadow, his work speaks to a humanistic approach. His designs are not about imposing a singular aesthetic but about crafting experiences — products that feel lived in and familiar, yet wholly original.

Over the years, his design philosophy has evolved but never wavered. He defines his approach as ‘sensual minimalism’ — a balance of warmth, tactility, and reductive form. “I want to show the world that a contemporary physical environment can be soft, human, and pleasurable,” he says. It’s a philosophy evident in everything from his Voxel collection for Vondom — an exploration of angular yet inviting forms — to the Kosmos series for MIDJ, an ode to space-age optimism blended with the comfort of organic forms.

His disdain for specialisation has led him to a career that is impossible to categorise. From product design to interiors, branding to academic lecturing, he sees no reason to be confined to one discipline. “I have always admired creatives who touch every facet of visual culture,” he explains. “I promised myself that if I ever had my own practice, it would be broad. I wanted to shape the world around me in every possible way.”

With a practice that spans continents and time zones, he has embraced the digital age with characteristic enthusiasm. WhatsApp and Zoom now facilitate collaborations across the globe, allowing his studio to function as a truly international entity. “It’s marvelous,” he says simply. “Technology has given us the ability to create without boundaries.”

Reflecting on his most defining works, he points to a handful of projects that encapsulate his design ethos. The Bobble water bottle — a universally beloved object, embodies his belief in accessible, functional beauty. Method’s hand soap, with its sculptural yet practical form, demonstrated that good design could exist at an affordable price. And then there’s the Naples Metro — a project spanning nearly a decade, where design met infrastructure to create a space that was as aesthetically compelling as it was practical.

In his view, the greatest shift in design over the past few decades is consumer intelligence. “The average consumer is no longer passive,” he asserts. “People have access to unlimited information. They can compare, research, and educate themselves. Brands must now operate with greater transparency and innovation.” Technology, too, has transformed the landscape. From 3D printing to bioplastics, he sees endless opportunities for design to push boundaries. “If you’re not innovating, you’re not designing — you’re just styling.”

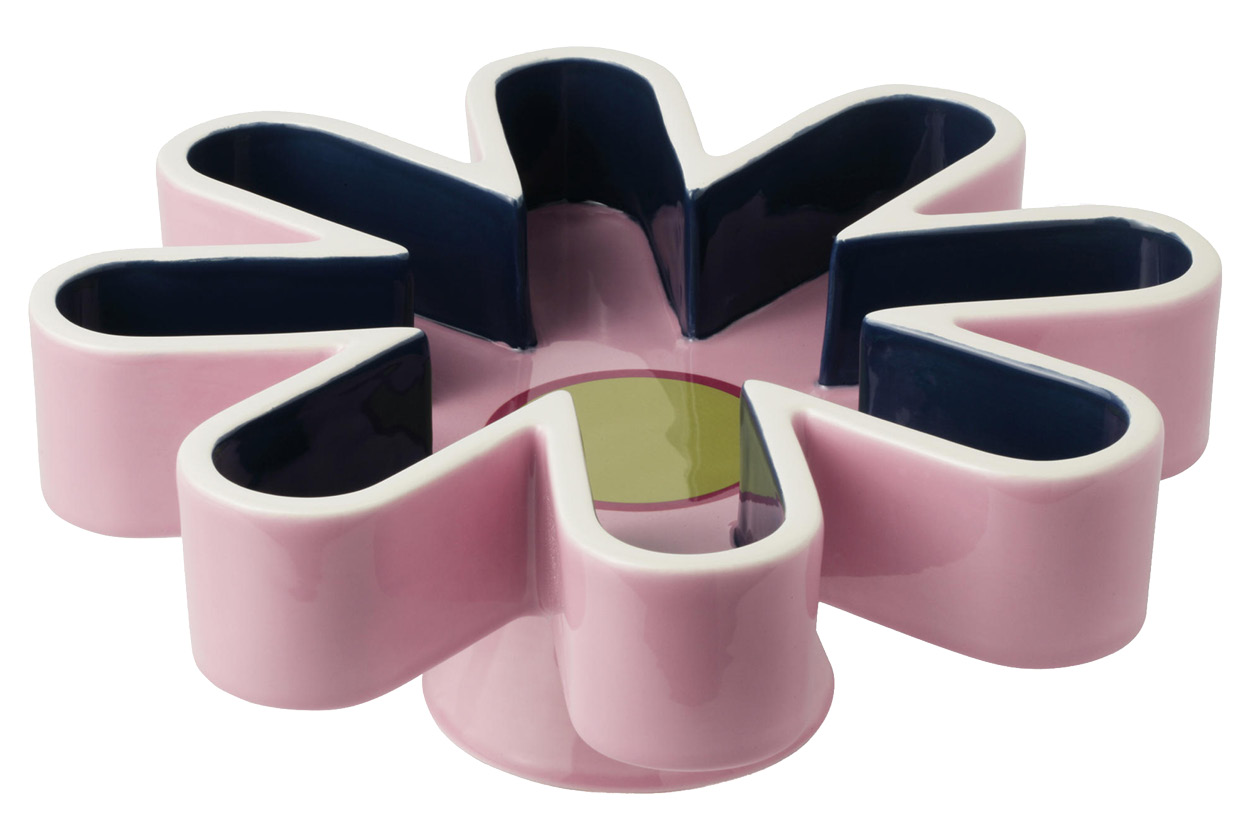

BowlKRB-5 for Bitossi BY KARIM RASHID from Matisse

For all the challenges that have come with his three-decade career — navigating business hurdles, protecting originality in a digital age, pioneering in a market that often resists change — he remains undeterred. His greatest lessons? That design is a collaborative act, a merging of minds and visions. That relationships — whether with clients, collaborators, or users — are at the heart of meaningful design.

Looking ahead, his schedule remains packed. New collaborations with Alessi, Natuzzi, and Vondom are on the horizon. A major re-brand of a heritage Austrian brand is in the pipeline. Architectural elements for private residences, new hotels across Europe, a bar redesign for Berlin’s Nhow Hotel are also occupying spaces in his mind. At any given time, his practice juggles upwards of 40 projects — each an opportunity to refine, redefine, and reimagine the physical world.

Through it all, his guiding tenet remains the same: design must serve. It must be human, innovative, and, above all, meaningful. In a world increasingly defined by fleeting trends, his work stands as a testament to enduring vision — one that shapes not just objects, but the way we live with them.