As the world turns its back on quiet luxury in favour of ostentation, our Editor Sjaan Askwith explores why it is that we’re all (once again) so infatuated with wealth and its signifiers.

Over the past few years, quiet luxury has defined how we dress, decorate our homes, and, in a more holistic sense, how we operate in the world (fashion and design are, after all, a comment on the moment in time). What began as a trend in the world of luxury fashion — with those who could afford to buy in deviating from the overly-showy, logo-emblazoned wares of the early aughts, instead turning their attention to fashion that whispers about their deep pockets — soon became much more. As trends often do, quiet luxury usurped its fashion-centric beginnings to become a way of life. And, until now, it represented a wider ethos by which many lived, turning the dial from perpetually online and open for public consumption towards a more under-the-radar approach.

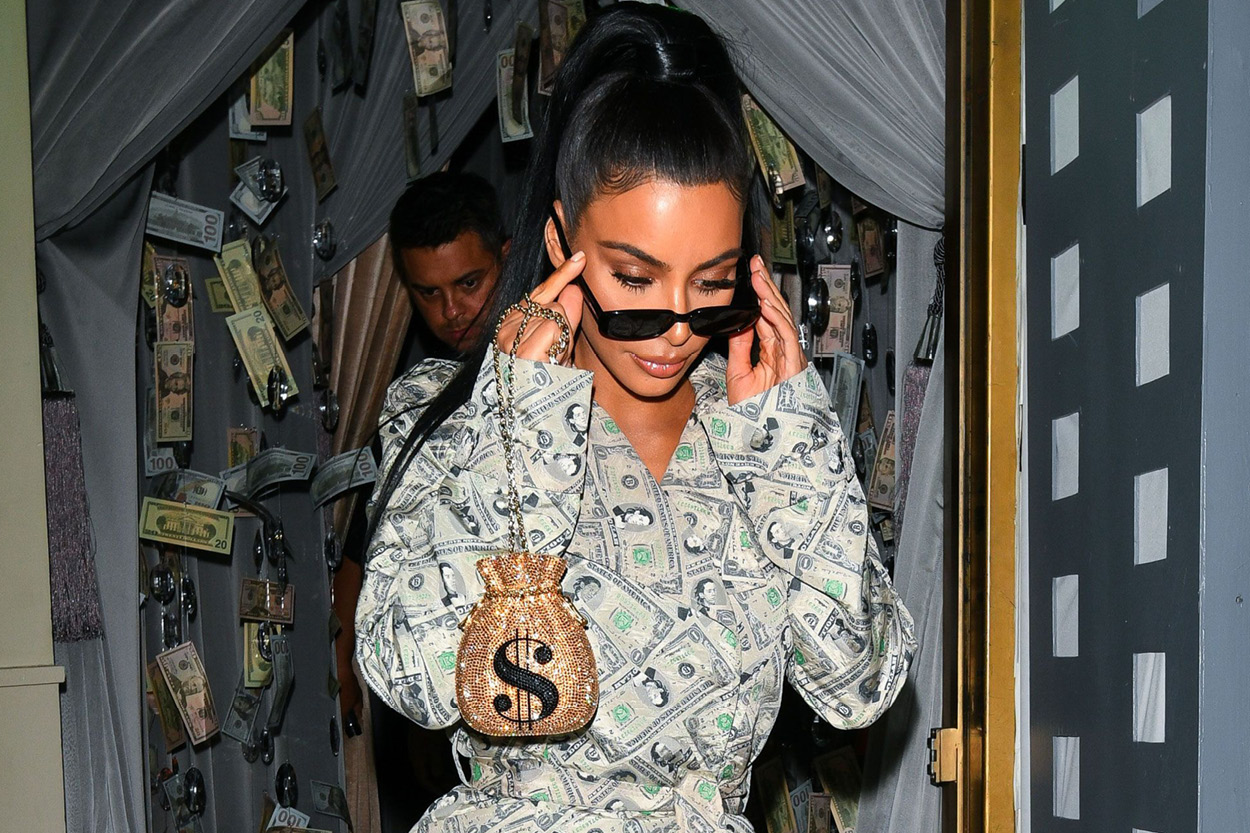

But, somewhere along the way, as it almost always does, the tides turned. The whispers of old money elegance or ‘stealth wealth’, with its muted cashmeres à la The Row and logo-less leather, began to give way to a new era of gaudiness, one that has less to do with discernment and discretion, and more to do with status and spectacle. The term ‘boom boom’ has been coined by cultural commentator Sean Monahan to describe this shift — a return to the brash, bold, and unabashedly wealthy aesthetic that defined the late ‘90s and early 2000s. If quiet luxury was the cultural manifestation of post-pandemic minimalism and restraint, ‘boom boom’ is its antithesis: excess, hyper-consumption, and a display of wealth in its most obvious forms.

At least part of this shift (which, it should be noted, is concerning at best and dangerous at worst) can likely be attributed to the new administration and its far-right amplification of capitalism’s most conspicuous expressions. The administration’s rhetoric of power and prosperity for those who play the game well enough — or manipulate it cleverly enough — has coincided with a resurgence of wealth as the ultimate signifier of status. And, while one may argue that the ultra-wealthy have always existed as a cultural fascination, never before have we been so invested in watching their lives play out, from the ‘real-time’ access of social media to the cinematic elevation of their excess in film and television.

The Kardashians are an obvious example. Long before society’s most recent wealth obsession and the rise of the nepo baby set, the family served as a bellwether for society’s shifting attitudes towards money. Their empire was built on their ability to monetise every aspect of their personal lives, and in doing so, they made wealth something not just to aspire to, but — and this is the clincher — consume. With over one billion Instagram followers between them, their influence is undeniable, their audience insatiable. Each post, each story, each glimpse into their diamond-dotted worlds fuels our collective fixation on the lives of the hyper-rich.

But it’s not just social media that has deepened our monetary obsession. Shows like Succession, The White Lotus, Rivals, The Perfect Couple and Netflix’s newest debut, Running Point, have transformed the wealthy into entertainment, portraying the mega-rich — almost always generationally so — as both grotesque and aspirational. Looking even further back into history, The Great and The Crown sung a similar tune. We despise their entitlement, their ignorance, their moral failures — and yet, we can’t look away. The same principle applies to the enduring appeal of The Real Housewives franchise — a spectacle of excess that offers a voyeuristic thrill in watching the extremely wealthy bicker, self-destruct, and make a mess of their seemingly picture-perfect lives. In many ways, these shows function as modern-day fables, offering up morality tales about money, power, greed, and the inherent demise that often follows. But, although many will be hesitant to admit it, there’s also an element of reluctant worship woven into our viewing. The sheer scale of their wealth remains something to marvel at, dissect, and devour.

Unsurprisingly, the luxury market has pivoted to cater to society’s growing hunger for ‘overt wealth’. Logos are back in full force, as is fur, with brands like Gucci, Balenciaga (which, ever the early adopter, sent out wads of faux cash as invites to its spring 23 show), and Louis Vuitton reclaiming maximalist aesthetics. Luxury’s quiet whisper is increasing in volume, fast.

So, why this significant shift? Why the renewed appetite for wealth as both spectacle and splendour? Perhaps the widening gap between the rich and the rest are to blame. The fact that financial security is slipping further from reach for many, making wealth an even more potent fantasy. Or maybe (as I strongly suspect) it’s simply human nature — the perpetual allure of shiny things, security, and the idea that money grants access to a simpler, less worrisome world just out of reach. The ‘boom boom’ trend may be cyclical; another iteration of history repeating itself, but its current faculty speaks to something that has endured throughout history: an eternal fascination with the aesthetics, power, and influence of extreme wealth.

For now, the pendulum has swung decisively in favour of ostentation. Whether reveling in the absurdity of the ultra-rich, admiring their privilege from afar, or plotting how to join their ranks, one thing is clear: society’s obsession with wealth is far from fading.